An aqueduct is a water supply or navigable channel constructed to convey

water. In modern engineering, the term is used for any system of pipes,

ditches, canals, tunnels, and other structures used for this purpose.

In a more restricted use, aqueduct (occasionally water bridge) applies

to any bridge or viaduct that transports water - instead of a path, road

or railway - across a gap. Large navigable aqueducts are used as

transport links for boats or ships. Aqueducts must span a crossing at

the same level as the watercourses on each end. The word is derived from

the Latin aqua ("water") and ducere ("to lead").

The Romans constructed aqueducts to bring a constant flow of water

from distant sources into cities and towns, supplying public baths,

latrines, fountains and private households. Waste water was removed by

the sewage systems and released into nearby bodies of water, keeping the

towns clean and free from noxious waste. Some aqueducts also served

water for mining, processing, manufacturing, and agriculture.

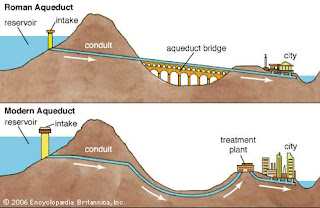

Aqueducts moved water through gravity alone, along a slight downward

gradient within conduits of stone, brick or concrete. Most were buried

beneath the ground, and followed its contours; obstructing peaks were

circumvented or less often, tunneled through. Where valleys or lowlands

intervened, the conduit was carried on bridgework, or its contents fed

into high-pressure lead, ceramic or stone pipes and siphoned across.

Most aqueduct systems included sedimentation tanks, sluices and

distribution tanks to regulate the supply at need.

The

Romans enjoyed many amenities for their day, including public toilets,

underground sewage systems, fountains and ornate public baths. None of

these aquatic innovations would have been possible without the Roman

aqueduct. First developed around 312 B.C., these engineering marvels

used gravity to transport water along stone, lead and concrete pipelines

and into city centers. Aqueducts liberated Roman cities from a reliance

on nearby water supplies and proved priceless in promoting public

health and sanitation. While the Romans did not invent the

aqueduct—primitive canals for irrigation and water transport existed

earlier in Egypt, Assyria and Babylon—they used their mastery of civil

engineering to perfect the process. Hundreds of aqueducts eventually

sprang up throughout the empire, some of which transported water as far

as 60 miles. Perhaps most impressive of all, Roman aqueducts were so

well built that some are still in use to this day. Rome’s famous Trevi

Fountain, for instance, is supplied by a restored version of the Aqua

Virgo, one of ancient Rome’s 11 aqueducts.

Rome's first aqueduct supplied a water-fountain sited at the city's

cattle-market. By the 3rd century AD, the city had eleven aqueducts, to

sustain a population of over 1,000,000 in a water-extravagant economy;

most of the water supplied the city's many public baths. Cities and

municipalities throughout the Roman Empire emulated this model, and

funded aqueducts as objects of public interest and civic pride, "an

expensive yet necessary luxury to which all could, and did, aspire."

Most Roman aqueducts proved reliable, and durable; some were maintained

into the early modern era, and a few are still partly in use. Methods of

aqueduct surveying and construction are given by Vitruvius in his work

De Architectura (1st century BC). The general Frontinus gives more

detail, in his official report on the problems, uses and abuses of

Imperial Rome's public water supply. Notable examples of aqueduct

architecture include the supporting piers of the Aqueduct of Segovia,

and the aqueduct-fed cisterns of Constantinople.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment